2. Belarus’s national animal is the European Bison, an animal that nearly went extinct but has made a comeback

The European bison is the national animal of Belarus. The animal is also known as the wisent.

After near extinction, conservation efforts in the country helped the European bison recover. In 1952, two European bison were released to the wild. Today there are over two thousand, according to the Nature Conservatory.

Conservation efforts in the 20th century reintroduced the species to the Białowieża Forest, with populations growing since then.

Bonus Facts About Belarus: The green stripe on the flag represents its forests.

Who knows? Maybe you’ll save a species through conservation efforts in your local area.

Fun Facts About Belarus – The Return of the European Bison

What’s the difference between Białowieża Forest and Belovezhskaya Pushcha National Park?

The difference between Białowieża Forest and Belovezhskaya Pushcha National Park is that Bialowieza Forest is the entire forest spanning Belarus and Poland, while Belovezhskaya Pushcha National Park specifically refers to the Belarusian part of the forest.

Approximately two-fifths of Belarus is forest covered. The Białowieża Forest is a UNESCO World Heritage site and one of Europe’s remnants of the wild, forested European plain.

Visiting Belovezhskaya Pushcha National Park

- Getting There: Belovezhskaya Pushcha is 60 km north of Brest and accessible via car, public bus, or organized tours. Vehicles require special permits to enter the park.

- Where to Stay: Hotels at the park, nearby guest cottages, or accommodations in Brest.

3. Belarus is famous for potato dishes, but it’s more than just that

Potatoes are a big part of Belarusian cuisine and there are at least 45 different dishes made from them. The Belarusian national dish is draniki, a potato pancake. “Draniki” comes from the Belarusian and Russian word meaning “torn up” or “shredded”.

Some other popular Belarusian potato dishes include Babka (potato casserole), Tsibriki (bite-sized potato balls), Kletski (potato dumplings) and Kartofel’nyk (layered potato cake).

Analysis of Potato Usage in Belarusian Recipes

To understand the importance of potatoes in Belarusian cuisine, we analyzed 202 Belarusian recipes in the cookbook Belarusian Cuisine Miensk: Uradžaj, 1994 (Compilation by L. Dzierbičava, 1977).

![Yellow book titled Belarusian cuisine with drawing of a flower.]()

Belarusian cuisine. Miensk: Uradžaj, 1994. (Compilation. L.Dzierbičava, 1977.)

Conventional wisdom suggests Belarusian food is dominated by the potato. However, our analysis shows that out of 202 recipes, only 45 recipes used potatoes as a main ingredient, making them less prevalent in the cuisine than widely believed.

In fact, other ingredients appeared more frequently:

- Onions: 45% (appeared in 90 out of 202 recipes)

- Eggs: 41% (appeared in 83 out of 202 recipes)

- Flour: 36% (appeared in 72 out of 202 recipes)

- Butter: 35% (appeared in 70 out of 202 recipes)

Flour Outshines Potatoes in Belarusian recipes

![Starch-heavy vs potato-heavy bar graph of Belarus.]()

Our findings revealed that flour-heavy recipes outnumbered potato-heavy ones. The data shows a reliance on flour-based ingredients such as wheat flour, rye flour and bread, with 53 recipes classified as flour-heavy compared to 26 as potato-heavy.

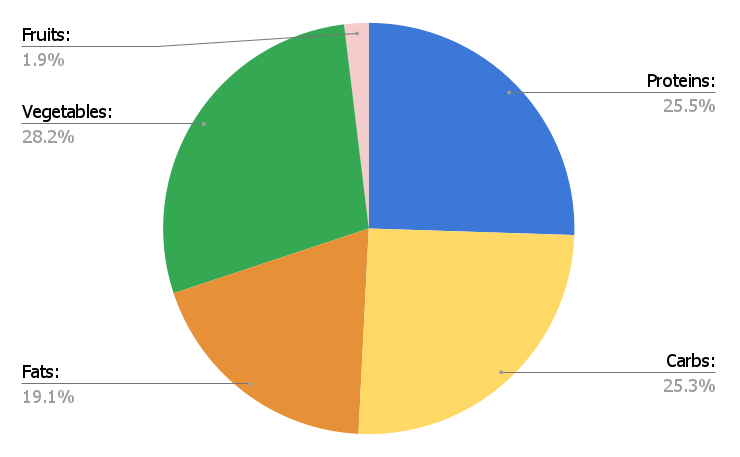

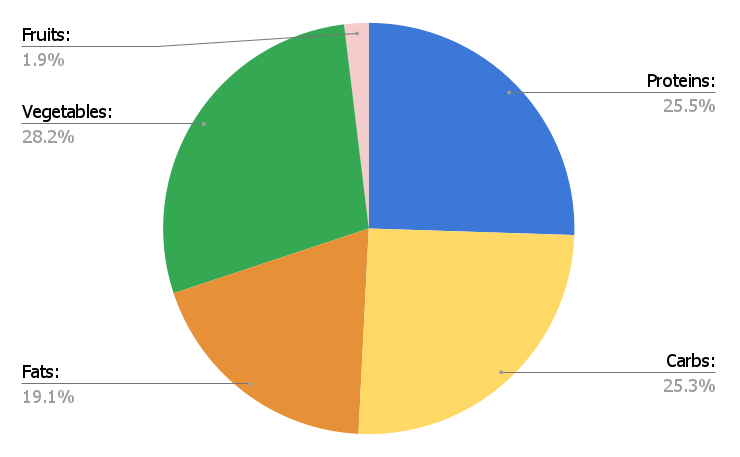

Nutritional Balance in Belarusian Food : Veggies FTW!

Belarusian recipes prioritize vegetables over starches or proteins, challenging the stereotype of Belarusian cuisine being starch dominant.

Our analysis shows the cuisine achieves a balance, with nearly equal contributions from proteins and carbohydrates, complemented by moderate fat content and minimal reliance on fruits.

Belarusian Recipes Tend Toward Simplicity

According to Rustic Pathways’s data, Belarusian recipes are straightforward, averaging 6.4 ingredients per recipe. Only 7 recipes out of 202 used more than 10 ingredients and even these more “complex” dishes relied heavily on staple ingredients like carrots, onions, flour, sour cream and potatoes.

Ingredient Pairings in Belarusian Recipes

Our analysis of ingredient pairings showed that Belarusian recipes often use a few key staples:

Limitations of our Analysis

Our analysis is based on 202 recipes from one cookbook. While this is a substantial sample, it may not fully represent Belarusian cuisine as a whole. Further approaches should expand on regional influences and compare staples across countries.

Summary of Rustic Pathways Analysis of Belarusian Cuisine

Belarusian cuisine is more than just potatoes. Our analysis reveals a practical food culture that prioritizes vegetables, proteins and simplicity. Flour-heavy recipes outnumber potato-based ones, and staple ingredients like eggs, onions and butter dominate pairings.

This data-driven perspective challenges common assumptions and provides a more accurate picture of what type of food you’ll be eating if you travel to Belarus.

Our verdict: It’s not just potatoes.

4. Independence Avenue in Minsk is the longest street in the country

Independence Avenue is the main thoroughfare in the capital city, Minsk. Praspiekt Niezaliežnasci, in the local language, stretches for 9.3 miles (15 kilometers) and crosses five different memorial squares: Kalinin Square, Yakub Kolas Square, Victory Square, October Square and Independence Square.

The stroll down Independence Avenue passes you by important government buildings and cultural institutions such as the House of Representatives of the National Assembly, State Security Committee of Belarus and The National Library of Belarus.

What to do on a walk down Independence Avenue in Minsk

Walk West to East and enjoy the city. The 6 mile (10 kilometer) walk with stops can take an entire day in Minsk.

If you get tired, ride back on the Moscow line (Metro Line 1) of the Minsk Metro which roughly follows the same route. The metro is denominated in Belarusian rubles; a one-way subway pass is 0.90 BYN (90 kopecks or roughly $0.27). The metro runs until 12:40 AM, but the schedule varies by season.

- House of Representatives of the National Assembly of the Republic of Belarus, Ulitsa Sovetskaya 11, Minsk, Minskaja voblasć, Belarus

- Independence Square, Minsk, Minsk, Minskaja voblasć, Belarus

- GUM Department Store, prasp. Niezaliežnasci 21, Minsk, Minskaja voblasć, Belarus

- State Security Committee of Belarus, prasp. Niezaliežnasci 17, Minsk, Minskaja voblasć, Belarus

- October Square, Minsk, Minskaja voblasć, Belarus

- Minsk Planetarium, vulica Frunze 2, Minsk 220088, Belarus

- Victory Square, Minsk, Minskaja voblasć, Belarus

- Čaliuskincaŭ Park of Culture and Recreation, prasp. Niezaliežnasci, Minsk, Minskaja voblasć, Belarus

- National Library of Republic of Belarus, prasp. Niezaliežnasci 116, Minsk, Minskaja voblasć 220114, Belarus

- Holy Trinity Church, Kalinovskogo 119, Minsk, Minskaja voblasć 220086, Belarus

Independence Avenue in Minsk, Belarus

5. The History of Belarus from 1569 to today

Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569-1795)

The Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth was one of the largest nation-states in Eastern Europe from 1569 to 1795. Its governance system was known as “Golden Liberty,” a proto-democratic, decentralized structure that granted significant power to the nobility.

The system was innovative in the era of absolute monarchs but left the Commonwealth slow to respond to external threats.

The Commonwealth fought three wars against increasing Russian incursion and influence in the late 1700s. They lost all three, and with each a portion of the territory was partitioned to the victors.

Through the First, Second, and Third Partitions, the empires of Russia, Prussia, and Austria carved up the Commonwealth’s lands, erasing it as an independent state in 1795.

- Russia annexed most of modern-day Belarus, eastern Lithuania, and western Ukraine.

- Prussia acquired central Poland.

- Austria gained southern Poland.

Russian Empire in Belarus (1795-1917)

After the Third Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795, the Russian Empire absorbed Belarus’s land. These territories were reorganized into the governorates of Minsk, Vitebsk, Mogilev, and Grodno, forming the Northwestern Krai, or subdivision.

The Russians pursued a Russification policy designed to erase its Belarusian cultural identity. Schools taught exclusively in the Russian language. The Belarusian language was marginalized, with restrictions on its public use and publication, culminating in the ban on Belarusian books in 1859.

Further, the Uniate Church was abolished in favor of Eastern Orthodox Christianity as the main religion.

Despite this, Belarusian cultural resistance persisted, often intertwined with broader Polish-Lithuanian uprisings, as seen in the revolts of 1830-31 and 1863-64.

The 1863 uprising was led by figures like Kastus Kalinowski and marked a breaking point. Kalinowski’s newspaper, Mużyckaja prauda (Peasants’ Truth), appealed directly to peasants, combining calls for social justice with a sense of national identity.

Functionally, Russia’s efforts of suppression planted the seeds for Belarusian identity.

Early Soviet Period (1917-1939)

The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution transformed Belarus. In 1918, local movements established the Belarusian People’s Republic (BPR), Belarus’s first attempt at independent modern statehood.

But, while the BPR had the support of the nationalists, intellectuals, radicals and activists in Minsk, it had limited public support given that most of Belarus’s population lived in rural areas. Between this and the competing influence of Bolsheviks in Russia, the BPR failed.

By 1919, Bolshevik forces crushed the independence movement, incorporating Belarus into the short-lived Lithuanian–Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic before establishing the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Under Joseph Stalin’s First Five-Year Plan (1928–1932), Belarus underwent industrialization. Factories were constructed in Minsk and Mogilev, while Vitebsk became a center for textile production.

Urban migration surged. Minsk’s population tripled between 1926 and 1939 and the share of the population in urban areas rose from 15% to 27%.

During the 1920s, the Belarusian language gained official status and experienced a brief cultural revival as part of the Soviet policy of “korenizatsiya” (indigenization). However, this period ended in the 1930s when Stalin reversed these policies, favoring Russification.

An influx of workers from Russia during industrialization further entrenched Russian language and culture, particularly in urban centers and government institutions.

World War II and Its Impact (1939-1945)

The Second Great War devastated Belarus. During the German occupation from 1941 to 1944, it’s estimated that 2.3 million people died or 25% of Belarus’s population, the highest per capita loss of any nation in World War II. These numbers include soldiers and civilians alike.

The Jewish community suffered catastrophic losses, with 800,000 Belarusian Jews, 90% of the pre-war Jewish population, murdered in the Holocaust.

During the French invasion of Russia in 1812, the Belarusian people sabotaged the invading Napoleonic forces. A century later the resistance again emerged, but on a much broader scale. This time 300,000 Belarusian partisans conducted guerilla warfare sabotage operations against German Nazi forces.

German forces destroyed universally: cities, villages, and businesses. The occupation nearly eliminated Belarus’s pre-war intellectual elite, devastating the foundations of Belarusian culture.

Both Belarus’s infrastructure and society required complete reconstruction. After liberation from the Germans in 1944, Belarusians rebuilt their country, under Soviet rule.

Post-War Reconstruction and Soviet Era (1945-1991)

The post-war period marked Belarus’s emergence. The country was a founding member of the United Nations (as part of the Soviet Union). Belarus underwent reconstruction, and Soviet authorities prioritized industrialization in the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Minsk was a model Soviet city and Belarus became a major manufacturing center in the western USSR.

Russia’s influence grew as industrialization attracted immigrants from across the Soviet Union after the Second World War. Russian became the dominant language in cities and institutions.

The government promoted Soviet-centered identity and exercised control over Belarusian cultural expressions.

In 1986 the Chernobyl nuclear disaster occurred just 16 miles (26 km) from Belarus’s southern border. The catastrophe contaminated 70% of Belarus with nuclear fallout, affecting 23% of the country’s territory. The disaster created severe and lingering long-term health challenges including high cancer rates and genetic abnormalities.

Belarus as an Independent Nation (1991-Present)

On 25 August 1991, amid the Soviet Union’s collapse, Belarus gained independence alongside other former Soviet republics. The country faced immediate challenges transitioning to an independent country. In 1994, Belarus signed the Budapest Memorandum, surrendering its nuclear weapons in exchange for international security assurances.

The democratic election of Alexander Lukashenko as president in 1994 marked a turning point. His administration established a Soviet style authoritarian system, including state control over major industries and suppression of political opposition.

Modern Belarus walks a diplomatic tightrope. While seeking limited economic cooperation with the European Union, Belarus retains its strong ties to Russia, which accounts for 48% of its foreign trade. Russia maintains military facilities on Belarusian soil.

Belarus preserves Soviet monuments, maintains Russian as an official language alongside Belarusian.

Lukashenko still leads Belarus.

UNESCO World Heritage Site List in Belarus

Bialowieza Forest

Bialowieza Forest is a protected forest in Belarus and Poland that is home to the largest herd of European bison.

Mir Castle Complex

Mir Castle Complex is a renovated 16th century Gothic-style castle in Central Western Belarus with Renaissance and Baroque elements. You can stay there.

- Address: Krasnoarmeyskaya Ulitsa 2, Mir, Hrodna Region 231444, Belarus

- Hours: Monday – Sunday: 10 a.m.–6 p.m. December 24, December 31, January 6: 10 a.m.–5 p.m. January 1st, 2025: Closed.

- Tip: The ticket office closes 40 minutes before the museum’s closing time. There’s a hotel on the site where you can stay overnight.

Radziwill Complex at Nesvizh (Nesvizh Radziwiłł Castle)

The Radziwill Complex at Nesvizh is a castle, church and township in central Belarus associated with the Radziwill family. The set of buildings shaped Central European and Russian architecture.

- Address: Lieninskaja vulica 19, Niasviž, Minskaja voblasć 222603, Belarus (Museum Address).

- Hours: 10 a.m.– 7 p.m.

- Tips: Give yourself four hours at least for the castle, grounds and museum. The scale and beauty of this place are staggering. There are guided tours, but you can also go on your own. Get tickets at the entrance or book at least two weeks in advance for groups.

Struve Arc

The Struve Geodetic Arc is a triangulation chain that stretches through ten countries from Norway to the Black Sea. It provided the first accurate measurement of a meridian arc and helped scientists determine Earth’s size and shape.

- Note: We do not recommend visiting the Struve Arc Belarus. The Struve location in the Observatory in Tartu, Estonia is excellent.

References